And let's be very clear, I don't mean that NWS forecasts are getting less skillful. They are getting better. But it is clear that the NWS has fallen behind the state-of-the-art and is not producing as skillful or useful products as it could or should.

This blog will consider the role of human forecasters in the NWS and how the current approach to prediction is a throwback to past era. As a result forecasters don't have time to take on important tasks that could greatly enhance the quality of the forecasts and how society uses them.

Let me begin by by showing you a comparison of forecast accuracy of the NWS versus major online weather sites, such as weather.com, weatherunderground.com, accuweather.com, and others. This information is from the web site https://www.forecastadvisor.com/, which rates the 1-3 day accuracy of temperature and precipitation forecasts at cities around the nation. I have confirmed many of these results here in Seattle, so I believe they are reliable. I picked three locations (Denver, Seattle, and Washington DC) to get some geographic diversity. Note that the NWS Digital Forecast is the product of NWS human forecasters.

The National Weather Service forecasters are not in the top four at any location for either the last month or year, and forecast groups such as The Weather Channel, Meteogroup, Accuweather, Foreca, and the Weatherunderground are in the lead. And these groups have essentially taken the human out of the loop for nearly all forecasts.

Or we can take a look at some of the NWS own statistics. Here are the mean absolute errors for surface temperature for forecast sites around the U.S., comparing U.S. forecasters (NDFD), the old U.S. objective forecasting system called MOS (Model Output Statistics) that does statistical post-processing to model output, and a new NWS statistical post-processing system called National Blend of Models (NBM). Lower is better. The blend (no humans involved) is as good or better than the forecaster product for forecasts going out 168 h

12-h precipitation? The objective blend is better (lower is better on this graph).

I could show you a hundred more graphs like this, but the bottom line is clear: human forecasters, on average, can not beat the best objective systems that take forecast model output and then statistically improve the model predictions.

Statistical post-processing of model output can greatly improve the skill of the model predictions. For example, if a model is systematically too warm or cold at a location at some hour based on historical performance, that bias can be corrected. (reminder: a computer forecast model solves the complex equations the describe atmospheric physics)

National Weather Service forecasters spend much of their time creating a

graphical rendition of the weather for their areas of responsibility. Specifically, they use an interactive forecast preparation system (IFPS) to construct a 7-day graphical representation of the weather that will be distributed on grids of 5-km grid spacing or better. To create these fields, a forecaster starts with model grids at coarser resolution, uses “model interpretation” and “smart” tools to combine and downscale model output to a high-resolution IFPS grid, and then makes subjective alterations using a graphical forecast editor.

Such gridded fields are then collected into a national digital forecast database (NDFD) that is available for distribution and use. The gridded forecasts are finally converted to a variety of text products using automatic text formatters.

So when you read a text NWS forecast ("rain today with a chance of showers tomorrow"), that text was written by a computer program, not a human, using the graphic rendition of the forecast produced by the forecasters.

But there is a problem with IFPS. Forecasters spend a large amount of time editing the grids on their editors and generally their work doesn't produce a superior product. Twenty years ago, this all made more sense, when the models were relatively low resolution, were not as good, and human forecasters could put in local details. Now the models have all the details and can forecast them fairly skillfully.

And this editing system is inherently deterministic, meaning it is based on perfecting a single forecast. But the future of forecasting is inherently probabilistic, based on many model forecasts (called an ensemble forecast). There is no way NWS forecasters can edit all of them. I wrote a peer-reviewed article in 2003 outlining the potential problems of the graphical editing approach...unfortunately, many of these deficiencies have come to light.

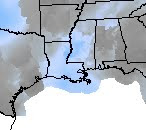

Another issue are the "seams" between forecast offices. Often there are differences in the forecasts between neighboring offices, resulting in large changes at the boundaries of responsibilities...something illustrated below by the sky coverage forecast for later today:

Spending a lot of time on grid editing leaves far less forecaster time for more productive tasks, such as interacting with forecast users, improving very short-term forecasting (called nowcasting), highlighting problematic observations, and much more.

But what about the private sector?

Private sector firms like Accuweather, Foreca, and the Weather Channel all use post-processing systems that descended from the DICast system developed at the Research Application Lab (RAL) of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). DICast (see schematic below) takes MANY different forecast models and an array of observations and combines them in an optimal way to produce the best forecast. Based on based performance, model biases are reduced and the best models given heavier weights.

This kind of system allows the private sector firms to use any input for their forecasting systems, including the gold-standard European Center model and their own high-resolution prediction systems, and is more sophisticated than the MOS system still used by the National Weather Service (although they are working on the National Blend).

The private sector firms do have some human forecasters, who oversee the objective systems and make adjustments when necessary. The Weather Channel folks call this "Human over the Loop".

The private is using essentially the same weather forecasting models as the NWS, but they are providing more skillful forecasts on average. Why? Better post-processing like DICast.

Machine Learning

DiCast and its descendants might be termed "machine learning" or AI, but they are relatively primitive compared to some of the machine learning architectures currently available. When these more sophisticated approaches are applied, taking advantage of the increased quality and quantity of observations and better forecast models, the ability of humans to contribute directly to the forecast process will be over. Perhaps ten years from now.

So What Should the National Weather Service Do?

First, the NWS needs to catch up with private sector in the area of post-processing of model output. For too long the NWS has relied on the 1960s technology of MOS, and the new National Blend of Models (NBM) still requires work. More advanced machine learning approaches are on the horizon, but the NWS needs to put the resources into developing a state-of-the-art post-processing capability.

Second, the current NWS paradigm of having a human be a core element of every forecast by laboriously editing forecast grids needs to change. The IFPS system should be retired and a new concept of the role of forecasters is required. One in which models and sophisticated post-processing take over most of the daily forecasting tasks, with human forecasters supervising the forecasts and altering them when necessary.

1. Forecasters will spend much more time nowcasting, providing a new generation of products/warnings about what is happening now and in the near future.

2. With forecasts getting more complex, detailed, and probabilistic, NWS forecasters will work with local agencies and groups to understand and use the new, more detailed guidance.

3. Forecasters will become partners with model and machine learning developers, pointing our problems with the automated systems and working to address them.

4. Forecasters will intervene and alter forecasts during the rare occasions when objective systems are failing.

5. Forecasters will have time to do local research, something they were able to do before the "grid revolution" took hold.

6. Importantly, forecasters will have more time for dealing with extreme and impactful weather situations, enhancing the objective guidance when possible and working with communities to deal with the impacts. 44 people died in Wine Country in October 2017 from a highly predictably weather event. I believe better communication can prevent this.

I know there are fears that the NWS union will push back on any change, but I hope they will see modernization of their role as being beneficial, allowing the work of forecasters to be much more satisfying and productive.